An excerpt from the book A Driven Mind by Garry Sowerby

The airport was empty except for a lanky individual sweeping the floor at the far end of the terminal. The scene had a surreal feel, especially considering my international flight was scheduled to leave in an hour.

The Kamikaze driver of the bent Peugeot taxicab that scared the life out of me during the ride from the Marriott Hotel in downtown Bujumbura had departed, grumbling something I assume was related to the puny tip I gave him. I was alone, save the sweeper.

Upon further investigation I encountered a ticket agent napping on a bench behind the Kenya Airways ticket counter.

“Err, excuse me, is there any sign of the flight from Nairobi? I’m supposed to catch the continuation of that flight to Dar es Salaam.”

“Oh, you must be Mr. Sowerby. You were the only one missing, so it left twenty minutes ago.” He was most apologetic.

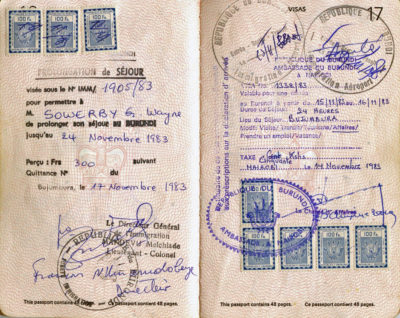

My partner Ken Langley was on the flight and I was supposed to fly on to the Tanzanian capital for meetings with the Canadian High Commission and officials from the Tanzanian Automobile Association. I had flown to Bujumbura, Burundi five days earlier and, with my mission completed, was anxious to move on.

It was November 18, 1984. Ken and I were on a month-long fact finding trip to determine the best routing through Africa for an assault on the land-speed record from the southern tip of Africa to the northern tip of Norway, high above the Arctic Circle. Our trek, dubbed the Africa-Arctic Challenge, was a sequel to the around-the-world-driving record we set in a Halifax-built Volvo in 1980.

We had scored a new GMC Suburban from GMC Truck Division of General Motors which we would use to establish a new Guinness world record for the Cape to Cape drive. The adventure would help GM launch a new 6.2-litre V-8 diesel engine it had recently introduced in its light trucks and full-sized SUVs. The quest was, to us, a high stakes affair to hopefully pay off the lingering financial shortfall on the 1980 global boondoggle and we figured a month’s reconnaissance of the hot-spots along our proposed route would prove a wise investment.

We had already visited contacts in Denmark, Greece, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Djibouti. In Kenya, Ken and I decided to split up for a few days, so he stayed in Nairobi while I flew to Burundi, a landlocked east-central African republic half the size of Nova Scotia, to investigate routings from Tanzania. If feasible, the short-cut would save us hundreds of kilometers on our trek through the continent.

In Bujumbura, the steamy lethargic capital city, I met with the president of the Automobile Club of Burundi who didn’t offer any solutions to our routing dilemma. He did however call a man who claimed to have contacts in the southern part of the country that would be able to provide the required information.

The next morning Mr. Collette, a jovial Belgian engineer, picked me up at the Marriott hotel. The humidity was ridiculous, and I was drenched in sweat by the time I strapped myself into his Toyota pick-up truck.

We maneuvered through the capital. A half hour south of the city, Mr. Collette stopped on the side of the road and fished a blindfold out of his briefcase.

“I hate to do this, but my contacts are very private people.” He seemed a little embarrassed.

We drove for about an hour. The road became rougher. Once in a while we would stop and Mr. Collette would talk to someone, in French once but mostly in a local dialect. I eventually dozed off and woke when my door opened.

“You can take that off now.” The blindfold was drenched in perspiration. Mr. Collette laughed as my eyes squinted trying to adjust to the bright sunlight like a kid stumbling out of an afternoon matinee.

We were parked in front of a magnificent white stucco house, by far the most prosperous-looking building I had seen since leaving Kenya. Inside, a servant led us into a cavernous room with a half-dozen lazy ceiling fans. A massive mahogany table was planted in the middle of the room.

Four men sat around the table in wing-back Victorian chairs. A fat Chinese man, a blonde American with a southern drawl, a slight Pakistani and a speedy African who did most of the talking. From his accent I assumed he had been educated in England.

Note pads covered in illegible scrawl and four pistols were the only things on the table. I naively wondered if they were loaded.

Everyone was cordial. We sipped black tea while I briefed them on our quest to drive from the bottom of Africa to the top of Europe in record time. My idea of a Burundi shortcut was immediately put to rest though. They told me there were routes but were adamant it would be very dangerous to travel trough the mountains of northern Tanzania and enter Burundi from that direction.

The meeting was over in 15 minutes. As Mr. Collette slipped the sweaty blindfold back across my eyes for the drive out of the jungle, I assured him the Burundi shortcut would be deleted from the routing options.

We arrived back at the hotel just in time for the white-knuckle taxi ride to the airport to catch the plane that had left an hour and twenty minutes early.

“How long before the next flight to Tanzania?” I asked the dozy Kenya Airways ticket agent.

“Four days if the weather holds. There is a Marriott Hotel in the city with a lovely swimming pool.”

I walked through the deserted airport. The warped Peugeot taxi was parked out front beside a ‘no parking’ sign. I was tempted to ask if the driver if he knew any shortcuts to Tanzania.

Follow Garry on Instagram: @garrysowerby