An excerpt from the book A Driven Mind by Garry Sowerby

In 1984 Kuwait was the wealthiest country in the world per capita. Its port was the most efficient on the Persian Gulf, busy with tankers shipping out oil and freighters bringing goods into the hot Arabian market.

Everyone had a job on this patch of sand but a war between Iran and Iraq was a big problem. Iraq borders Kuwait and Iran’s invasion of Iraq was taking place near the Kuwait border, sixty miles north of its capital, Kuwait City.

The black clouds of war could sometimes be seen looming on the horizon.

We had napped, but not slept in 64 hours as we approached Kuwait City from the south in March of that year. Well into our attempt to set a new land-speed record between the south tip of Africa and the north cape of Europe at Nordkap, Norway, we were optimistic but nervous.

A sandstorm in Saudi Arabia through which Ken Langley and I had pushed our 1984 GMC Suburban diesel truck impressed us and we thought another in war-torn southern Iraq would give us cover.

The American embassy Iranian terrorist had recently bombed was across the street from the Hilton Kuwait City we checked into and, although executions of the Iranian perpetrators had been delayed, there was fear of attack by groups sympathetic to Iran.

Leaving Kuwait City for the 575-kilometre drive to Baghdad, Iraq the next morning, I scanned the surrounding terrain. Industrial Kuwait was sprawling and oil rigs on the horizon shimmered in the desert heat like a drug induced hallucination.

An item Ken read in the Kuwait Times newspaper at breakfast was running through his mind: “The Iranian buildup on the Majnoon Islands indicates their next move will be to sever road connections between Basra and Baghdad, the Iraqi capital.”

It was the road we were heading for, a main target of the Iranian offensive that had been predicted all spring but had still not taken place.

Traffic fell off as we approached the border and, for the last 40 kilometers, we had the highway to ourselves. Black smoke was blowing in from the direction of Basra, the Iraqi port on the Persian Gulf. Its refineries were being shelled by Iranian artillery dug in only ten miles from the city.

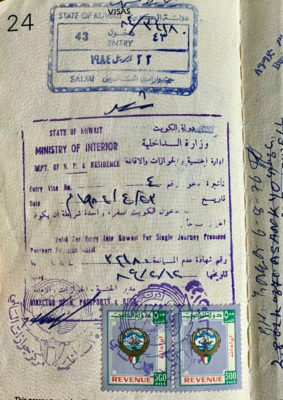

Clearing out of Kuwait went smoothly. The road through no-man’s-land to the Iraq line was littered with burned-out hulks of transport trucks, pick-ups and cars. At the frontier, a huge Welcome to Iraq billboard, followed by a Danger Ahead sign, greeted us.

There were a dozen lanes at the border post, six going in and six coming out, and off to the side were customs and immigration offices. Arabic music blasted from loudspeakers.

We handed our passports to the immigration officer, then sat down with a dozen truck drivers who’s dour looks spelled delay. But five minutes later we were through immigration and directed down the hall to Customs where a friendly woman with a beehive hairdo and the brightest red lipstick quickly did the paper work then sent us down another hall to pay a $25 so-called war insurance fee for the truck.

The post was closing at 4:00, just ten minutes away, when we were ushered into the Office of the Director of Customs. He was wearing pale blue pants and a shiny print shirt, the dress of the post complemented by the dark glasses that in themselves were like a uniform in the region.

“It’s too late,” the Director advised. “You’re going to have to stay here for the night.”

“We’re anxious to get going, ” I offered showing him news stories from Kuwait about our Africa-Arctic quest then offering to show him our truck.

When I pointed out bullet holes from an ambush in northern Kenya, he told us to get going since it was at least a six-hour drive to Baghdad.

Heading north our euphoria only lasted a few minutes. There were signs of war everywhere as we approached Basra. We passed a fertilizer factory with missile holes through its storage tanks. There were sandbag defenses, all manned, around the oil refineries and very little civilian traffic’’.

Carcasses of burned-out tanks and armored personnel carriers littered the shoulders of the two-lane highway. Columns of smoke rose on the horizon to the north, but in the midst of all this, the fields were filled with men, women and children harvesting tomatoes. They were smiling, as if war were a million miles away.

Meanwhile Ken drove while I scanned the eastern sky with binoculars looking for Iranian fighter planes. We had been told the Iranians sometimes strafed the highway in the evening and if we came under attack to get out of the truck and hit the ditch, because the jets would go for the truck.

There were no attacks as we skirted Basra and we were soon on the heavily rutted asphalt road to Baghdad moving away from the danger zone.

Later a police car led us through a military marshalling area where soldiers cheered, realizing from the sponsor decals on the Suburban that we were in some kind of race. There were thousands of soldiers there. Some, obviously returning from the front, wore torn uniforms with bandages over where limbs had been amputated or blown off. Others wore fresh uniforms and shiny boots, preparing to go south to the battle.

It was obvious from the facial expressions of the parents, wives and children gathered who was saying hello and who was bidding farewell to their loved ones.

We rolled into Baghdad shortly after midnight relieved but exhausted. I asked a cab driver for directions to the Mansour Melia Hotel, but the route sounded impossibly complicated.

Neither of us had been in Baghdad before so Ken got into the taxi and I followed as the driver led me across the Tigris River to the hotel. Somehow, I felt safe following a randomly chosen taxicab through the streets of Baghdad.

The sights sounds and severity of the day might have been expected considering we were driving through a war zone, but my fleeting glimpse of the rawness and reality of war has stayed with me for a long time.

Follow Garry on Instagram @garrysowerby