TOKYO — This city of 30 million stretches as far as the eye can see, even from 350 metres in the air, and a tour such as ours could easily take an entire day.

We had six hours.

Ours was an ambitious plan: fortify ourselves with ramen before taking the subway to Tokyo Skytree, Senso-ji Temple, Akihabara and Shibuya — and then settling in for something called a ninja dinner at Ninja Akasaka restaurant, not far from the Imperial Palace.

Six hours and 22,643 steps (14.4 kilometres of walking) later, we had done it.

1 p.m.: Ramen

Ramen is a staple of Japanese lunches, and it’s not at all like the packages of noodles and salt that are dirt cheap at the dollar store.

Ramen, particularly the tonkatsu (pork) variety we enjoyed, starts with a rich, deep broth, to which chewy noodles — made all the chewier by a high alkaline content that preserves the molecular structure of the pasta as it cooks to perfection — are added.

Fresh vegetables combine with bits of tender pork and grated garlic and it’s all topped with ajitama, or a seasoned, medium-boiled egg. Delicious.

We found our ramen cleverly hidden in a lower part of Shinagawa station, where a handful of shops each sell a different version.

As is typical, the ramen shop is highly efficient: you purchase your meal ticket at a vending machine, choosing the broth (miso, tonkatsu or salt), serving size and choice of topping before awaiting a seat.

Ramen shops are typically tiny, with maybe 30 seats, and a lineup out the door.

Once seated, you hand your meal ticket to your server, who places it on the high counter in front of your seat. When ready, the cook brings your soup and you begin to slurp.

Slurping is not just allowed, it’s expected, as the air accentuates the flavour as it passes over the noodles and broth.

When you’re done, you leave. There’s no waiting for a bill, no waiting for change, as it’s already been paid. It’s not a place to linger, either. It’s also surprisingly cheap, considering the city: a dish of pork ramen runs between ¥800 and ¥1,200, or about C$10 to $15.

2:30 p.m.: Tokyo Skytree

We left the ramen shop and headed upstairs to buy our subway passes, which work out to a reasonable $20 for an entire day.

Two trains later, we got out at Oshiage, right at the base of the Skytree.

The Skytree might seem an anachronism in today’s age of streaming video and satellite delivery, but it still houses transmitters and antennas for about a dozen TV and radio broadcasters.

It was built after the original Tokyo Tower lost some of its effectiveness for broadcasting as skyscrapers grew up around it, blocking transmitted signals.

It is the tallest structure in Japan, tallest tower in the world and second-tallest structure in the world, just behind the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, U.A.E.

Construction of Skytree was completed in 2011 and it stands 634 metres (2,080 feet) high. Its height is symbolic, as the numbers six, three and four are represented in some forms of Japanese as mu, sa and shi, which, combined (Musashi), is the name of the area in which it is located. Plans were changed during construction to get the building to hit that symbolic height.

An engineering marvel, Skytree is designed for earthquake resistance. Reinforced concrete forms a central pillar, surrounded by a metal lattice that begins as an equilateral triangle at the base, gradually rounding to a circle at 350 metres. The lattice is fastened directly to the concrete until about 125 metres, at which point oil dampers are added to allow the lattice above to move independently from the concrete.

Like the CN Tower (which is almost 100 metres shorter), a prime source of revenue for Tokyo Skytree is tourism, with elevator tickets for the first observation deck (350 metres) about ¥2,000 (or C$25). A ticket to the Tembo Galleria (450 metres) is an extra ¥1,000 (about C$13).

The views from the first deck are stunning, with Mount Fuji, Mount Tsukuba, the Imperial Palace and Senso-ji Temple (our next stop) visible depending on weather.

4 p.m. Senso-ji Temple

Founded in 645 A.D., Senso-ji is the oldest Buddhist temple in Japan. What you see today is all largely rebuilt; the original buildings were bombed into oblivion in the Second World War, many having first been destroyed by the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

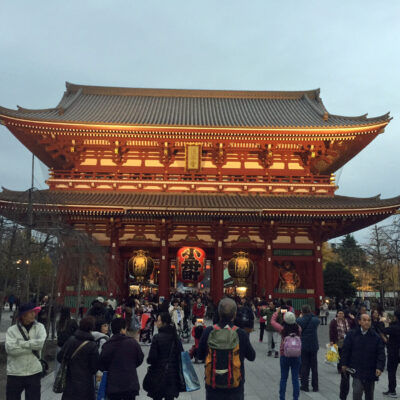

Located in Asakusa, it’s a short subway ride from Tokyo Skytree, all of one stop, actually, and then just a short walk to the Kaminarimon, the gate that begins your journey.

The Kaminarimon is adorned with a massive paper lantern in a vivid red and black paint scheme. From there, it’s about a quarter-kilometre walk through the Nakamise-dori, a collection of quaint shops offering everything from kimono to chop sticks to jewelry.

When we pass through that, we hear what sound like dice being shaken in a cup: we’ve hit one of the o-mikuji stalls. Here, for about ¥100 (a bit more than a dollar), you shake cans filled with slender sticks. Eventually, one of the sticks presents itself through a tiny hole in one end. It’s marked with a number and you find its corresponding drawer in the wall. Open the drawer and pull out a piece of paper. It’s like a fortune-cookie without the empty calories. Traditionally, having read the paper, you tie it to a rack of strings in front of the stall.

You pass through another gate, Hozomon, before you see the temple itself. In front is a Japanese equivalent to a First Nations smudge: a smouldering fire of wood and herbs kicking up a very aromatic smoke. Tradition holds that you can use your hands to direct the smoke to the site of an injury or malaise and the smoke will help it heal.

5 p.m. Akihabara

From Asakusa, it’s two trains to Akihabara, though the distance isn’t great. You transfer at Ueno to the Yamanote line and it’s then just two stops to Akihabara.

Here, you’ll find everything your electronics-loving heart can desire, from capacitors and resistors to project cases and volt-ohm meters. It is a Mecca to the world’s millions of amateur radio (or ham radio) buffs, and a popular stop for many who travel to Tokyo.

There’s also more here to feed than your inner geek, with restaurants, bars and other kinds of stores as well. There’s the Mother Farm milk bar, whose name conjures up images of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, but it’s not filled with droogs preparing themselves for a night of the old ultraviolence. It is, instead, a respectable ice cream parlour serving up soft-serve and milkshakes.

6 p.m. Shibuya

This area is home to the most photographed streets in the world, perhaps second only to New York’s Times Square. This is where Fast and Furious Tokyo Drift swerved through scores of pedestrians, and photographs of its bright store signs and advertising are as representative of Tokyo as the Eiffel Tower is of Paris.

There is virtually every high-end retailer you can imagine, and while you might not travel all the way to Tokyo to buy a Cartier, the buzz and nightlife surrounding the area is quite a draw. Come at night for the full effect.

7 p.m. Ninja Dinner

OK, no mincing words here. The concept for the Ninja Akasaka restaurant is intriguing, but poorly executed.

You enter a non-descript part of a rather ordinary office building through one small door. A “Ninja” leads you through a narrow passageway till you arrive — oh, the humanity! — at a part where the bridge is out. The “Ninja” waves his hand — and pushes a button — and a small drawbridge drops down. When you get across, he tells you to point your fingers at the bridge and say “Nin Nin,” at which point he pushes another button and the bridge goes up. A short, otherwise uneventful walk through the rest of the corridor ends inside the restaurant.

Let’s just say, this place isn’t appearing on World’s Wackiest Restaurants anytime soon.

The corny entrance comes off as an unpromising prelude, yet the dinner was actually quite delicious. Multiple courses, including some sushi, tempura, Wagyu beef, miso soup and a handful of other Japanese dishes, were all well-prepared and delicious. Our menu ranged in price from ¥10,800 to ¥14,800 (about $120 to $160) per person, depending on the size of your steak. Cheap, it’s not.

One thing that was quite Ninja-like was the service: place an empty beer glass near the door and very swiftly and stealthily it would be replaced. Also handy was a paging button somewhere at our table that would summon a waiter almost instantly.

Part of the evening also included a Ninja performing card tricks, none of which would be new to anyone who has watched Criss Angel, but they were expertly executed and left us with the right amount of “How’d he do that?”

After our lengthy journey, I’m left with two distinct impressions. One, I know why so many Japanese people are quite slender. They walk everywhere. Two, they’ll all soon be quite deaf!

At Akihabara, at Shibuya and in the casinos and pachinko parlours, the sounds and advertisements were stupefyingly loud. There’s subtlety in many parts of Japanese culture, just not in its marketing.